The plan for these two days in Frome was to

create some new glass piece, designed specifically for this project to afford

specific musical mappings. Scott and Shelley were joined by Sila (Shelley’s

intern) for two days in Sonja's workshop; and Rex Lawson joined us

briefly to see how his pianola rolls would transfer to glass.

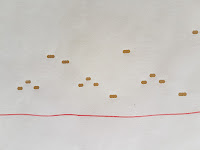

We had taken a motif

from a Bach fugue (no.2 in C minor) and sandblasted it onto the surface of a

glass 'embryo'; a basic glass jar shape. This embryo would have more molten

glass added to it so that the sandblasted dots would trap air bubbles under the

glass. The images below show the initial embryo, and a subsequent stage where

it has just been dipped in hot glass.

In preparation for this, Sonja had prepared

some embryos back in July. Shelley had done the painstaking work of

transferring the patterns from the pianola roll onto glass. This involved scanning

and adjusting the chosen designs from the rolls, cutting and re-cutting the

holes to etch the pattern into glass, then sandblasting and cleaning the glass.

As we arrived in Sonja’s workshop, she

showed us the embryos which had been slowly warming up all morning: they warm

up because if glass goes straight from room temperature to kiln temperature (over

1000°C) it would shatter. The plan for the session was to take the

various embryos, coat them in layers of molten glass (by ‘encapsulating’;

dipping into a cauldron of molten glass), and spin them out into flat plates.

In this way the etched patterns around the jar-shaped embryo would become a circular

pattern on a flat plate, captured beneath a layer of clear class that would

trap bubbles where the etched holes were.

Shelley had not done this for nearly two

years because it is so expensive. However, for this project it was perfect, because

the process of heating glass in a cauldron or ‘pot’ creates the most an

extraordinary ‘grain’ in the final object that is only visible with projected

or reflected light. This grant made it possible to create work using this

technique that suited our goals so well.

The scented autumn day finally arrived. Shelley

was was extremely nervous about how this might go. The whole process is almost

impossibly precarious, and made even more so by the thin-ness of the glass we

required. Shelley describes how she has ‘seen so many hours of hopeful effort

crack or fold or fall from the end of a blowing iron’.

And, as it happened, it did almost all go

horribly wrong, by Shelley’s original standards at least.

The first plate came out fine. The simple,

symmetrical pattern of the etched triplets spun out to create a series of

looping curves on the plate. Although clumsy and thick and deeply dipped in the

centre, it was at least in one piece; and round!

We tried a second plate, this time in black

glass. Rather than using black glass itself, the black is applied as a layer

onto clear class. The molten surface of the clear embryo (after dipping in

clear glass) is rolled in grains of black glass, which themselves melt and flow

into a layer. This particular granularity interacts with light in a wonderful

way, revealing a texture that is invisible to the naked eye. The image below

(by Michael Coldwell) was captured at our September session in

Leeds working with improvising musicians.

After these initial successes, our luck

began to run out. The first embryo of Tuesday morning had a complex

encapsulated pattern which threw the material off-centre to make a hopelessly

ridged and wobbly pancake. In the final heating, the edge of the glass caught

the rim of the glory hole to create yet another strange bump. However, under

strong light these imperfections have real charm.

The next embryo cracked and fell into the

pot of molten glass. Lost. Dear Sonja was so upset that her kind face burned

red and her solid assistant Keki stepped in to rake out the bubbly mess.

We started again – this time to make a plate.

In the next attempt the embryo collapsed

but stayed on the iron. Rather than try to retrieve the shape, I asked that we

simply let it be, a random looping stone form with my hard-won fugue pattern veering

around inside. We decided to stop trying for formal

precision and just play. Scott took this opportunity to do some glassworking,

to try and pull the glass into a shape that would respond well to the light.

The glass shape was quite dense, with the hot glass ‘gather’ loose, rolling and

looping like treacle on a spoon, but it was possible to pull the surface to

form some gentle twists, creating a beautiful and subtle ‘rabbit’ form.

For the final embryo we opted for a bubble

with twists. Now that he’d had a chance to get used to the feel of pulling the

soft glass with pliers, he had some specific ideas to try. Scott seemed totally

focused, pressing and pulling the material as it slowly came to rest. Sonja

blew a bubble (a hollow form which responds more easily to pulling) and added ‘prunts’

(handles) for Scott to experiment with twisting and pressing. The end result was

a slightly curved bubble with several twisting ‘knobbles’ on the surface. The

twists are barely visible in the glass itself, but create stunning caustics in

light (image Michael Coldwell).

Shelley’s intern, Sila also made a piece

for herself with patient coaching from Sonja. She has a rare gift for form and

edge and we look forward to seeing where she will go.

Reflecting on the whole day, we see this as

the event where the project took on a life its own, related-to but distinct-from

each of our personal practices. Shelley has described this way of working

together as being a ‘level of vulnerability and support that was both new and extremely

rewarding. Quite a revelation for me.’ Scott also found that after years of

discussing and the ideal, and working together in less than ideal circumstances

(brought about by distance, time, and trying to mould the project’s essence around

our existing practices and works) this activity of making new glass

specifically for the project gives it an independence that has both a

supportive force for both of us as artists, and it gives the project a ‘release’,

unmooring it from many previous concerns. For Scott especially, the act of

pulling and shaping the glass gave him a connection to the project’s materiality

that re-oriented his thinking about the musical possibilities. For both of us,

this new independence allowed us to relax some of our more discipline-specific

concerns about the project. For Shelley especially, the precision and rigour of

her usual practice had to be suspended as we experimented with forms. None of

the pieces we made in this session will be artworks in themselves, but they all

offer something to the project that we couldn’t achieve by using Shelley’s

other pieces. Scott’s discipline-specific concerns were destabilised

(positively!) later when we brought the finished pieces to Leeds to get some

musicians trying them out. More on this in the next blog post.