What an incredible week – two inspiring meetings with two

very different men – one an artist, the other a scientist - and yet so similar

in their passion and depth of knowledge – and both so generous with their time

and expertise.

We walked through the sunlit garden into a cavernous studio packed to the rafters with boxes of pianola rolls and presses and ancient computers to find Rex playing a grand pianola at full tilt – the piece that he played for their wedding exactly 12 years ago.

Rex explained how the design of the rolls evolved from 64 to 82 holes to allow for more sophisticated coding, and the difference between the European-style round holes and the American squares. He showed us how the additional lines and dots that I had seen in photographs online are used by the player as a guide for tempo and dynamics and demonstrated the surprising degree of freedom that the player can exert on the way the piece is ‘played’ by the machine.

Stravinsky, among other composers, personally supervised the notation and frontispieces for their new works. A stylised phoenix was the logo for one of the most influential publishers, the Aeolian Company. Rex has adopted this for the home page of his own remarkable software that allows him to design new rolls and cut them himself. He demonstrated the process for us, firing up an extraordinary machine with multiple pulleys and levers and a clattering array of hole punching bits.

|

Frontispiece for pianola roll

|

|

| Rex' software home page |

|

| Pianlola roll hole punch |

short video of hole punch in action

I had not realised that the whole pianola mechanism is essentially a set of air pipes – the holes release the vacuum and collapse a small set of bellows. This movement in turn releases a hammer which strikes the keyboard of the piano placed behind the pianola mechanism.

|

| pianola pipe system from the back |

|

| pianola pipe system from the front |

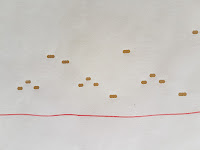

We chose Bach's Fugue no.2 in C minor from the first book of the Well Tempered Clavier. The recurring triplets of the central theme are coded as a distinctive triangular pattern that dances through the piece.

|

| triplet theme |

We left the Lawson household with warm agreement to meet

again. Rex will join us for the glassblowing session in Frome in September.

In the meantime, I will send him images of the work as it

progresses.

The second meeting was very different but equally memorable – I had met Michael Berry through my PhD supervisor several years ago. We had spent a wonderful afternoon at his house in Clifton discussing glass and caustics and he had kindly agreed to help in future projects.

I was delighted that he was able to spend an afternoon with us

when he is so much in demand. We all met at Trowbridge rail station and went to

a glassblowing studio run by two very talented young glass makers nearby.

Neither Michael nor Scott had ever seen the process at close quarters before

and seemed to find it fascinating despite the heat. James made some Prince Rupert’s drops for

Michael and showed us their new coldworking space before we went to a pub by

the canal in Bradford upon Avon to continue the conversation.

|

| Katie and James with Michael and Scott |

|

| Michael with a Prince Rupert's Drop |

|

| Scott with a Prince Rupert's Drop |

|

| Scott and Michael |

|

| Michael and I |

I had tried to read anything I could find on the internet about Caustics before meeting Michael but had become hopelessly confused. With his patient explanation, it all became perfectly clear – and brought Scott and my work into sharp focus.

Until now, we had been shining light through a revolving

object. This generated rich and complex patterns of light and shade especially

when combined with the reflections generated by the polished facets.

This was the heart of our original proposal– to understand

these phenomena to the point where we could direct and refine this luminous vocabulary

with greater creative intent.

As Michael explained, caustics are the patterns of light and

shade that are generated by a stream of photons interacting with small changes

in the angle of a shiny surface. These undulations essentially operate as

mini-lenses, focusing the beam to produce rich networks of curves and points.

The relationship between the scale of the topography and the

size of the beam is critical to the effect: a small beam such as a laser

pointer will be deflected by very small undulations, a large light source such

as an LED lamp will be deflected by larger-scale effects. In both cases, a

parallel beam is critical so that a stream of photons strikes the glass from

the same direction. A spreading or diffuse beam will create spreading and

diffuse effects.

We realised that in order to find the clarity and control we

were seeking, we should begin with flat rather than curved surfaces. Rather

than looking at the projections created by shining light through the piece, the

solution lay in the reflections.

We talked until it was time to get the train home – about parallels

between waves and rays of light and sound, the power of prime numbers and the

principle of natural beauty.

Michael kindly agreed to continue to advise us as the

project progressed.

I was so delighted to get back to the studio to run some experiments with

mouth-blown plates with sandblasted patterns to see whether we needed to silver the surface - and it seems that we don't need to after all, .

With Michael’s advice on the light source, have started to get some exciting results.

With Michael’s advice on the light source, have started to get some exciting results.